East falls ‘pre-history’: our predecessors, the Lenape

East Falls NOW, January 2023, by Rich Lampert

At the beginning of a new year, East Falls Historical Society is taking a look at the beginnings of our community – even before it was settled by Europeans.

Back in 1869, the historian Charles V. Hagner wrote, “Tradition says, and I have no doubt of the fact, that the Falls of Schuylkill was the last place deserted by the Indians who inhabited this part of the country; it being the head of tidewater, and consequently such fine fishing ground, had, of course, peculiar attractions for them. That it must have been a great resort of theirs, is proved by the fact of the innumerable Indian relics that have been found in the vicinity.” (You can find a digital copy (PDF, 2 Meg) of his book on our website, eastfallshistory.org.)

Since Hagner’s time, archeologists have discovered plenty of evidence to confirm that humans had been living in this area for hundreds of years before Europeans arrived on the scene in the 1600’s. These Native Americans were part of the Lenape, a group that modern scholars believe occupied a swath of land that included modern-day central and southern New Jersey, Eastern Pennsylvania, and territory as far south as Cape Henlopen in modern-day Delaware. They lived mostly along tributaries of the river they called the Lenapewihittuck, now called the Delaware. Of course, the tributaries included the Schuylkill River and its tributary, the Wissahickon Creek.

Robert Grumet, an anthropologist now affiliated with University of Pennsylvania, wrote that the Lenapes lived in a “complex but flexible network of closely related independent communities.” He says that early European settlers believed there were 8000-12,000 Lenape living across their overall territory, though later estimates are roughly double that.

The historian Jean Soderland writes that the Lenape lived in towns without town walls, with land held cooperatively rather than by individuals. The society apparently was egalitarian and democratic, with decisions made by consensus. Soderland goes on to say that before William Penn’s arrival in 1682, the Lenape and early European settlers “created a society with peaceful resolution of conflict, religious freedom, and collaborative use of the land and natural resources.” This society enabled prosperous trade among both Native and European inhabitants.

Despite this sunny description, there were plenty of clouds darkening life in the 17th Century. Soderland says that from the 1630s to the 1650s epidemics of smallpox and other diseases wreaked havoc on the Lenapes. Francis Daniel Pastorious, a leader in Germantown, wrote in 1694 that about 75% of the Lenape population had died in recent decades, and in 1697 two Swedish ministers indicated that Lenapes had become “very scarce” in the area.

The difficult times for the Lenape persisted. In 1742, according to the archeologist Herbert C. Kraft, the then-governor of Pennsylvania asked the surviving Lenape in the colony to pick up and move to the Susquehanna River valley, about 100 miles away – at least a few days’ trek. This was the first of many relocations. Descendants of the Lenape now live in Ohio, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and parts of Canada. In addition, according to the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania, many German immigrant men living in the Poconos married Lenape women, who were prized as wives because of their knowledge of the soil and farming techniques, and because of their strong work ethic. Many of their descendants still live in the Poconos and identify as Lenape.

People who identify as Lenape continue to live in and around Philadelphia, as well. Friends of the Wissahickon hosted a virtual program in October, 2020, with three members of the local Lenape community. The community actively reaches out to the wider public. For instance, one of the speakers, Shelley DePaul, is one of the few speakers of Native Lenape and has taught classes in the language at Swarthmore College and to private groups. Every three years, the Lenape hold a Rising Nation river journey, from Hancock, New York, to Cape May, New Jersey, a highly visible indication of their presence. And they are present digitally, at the website Lenape-Nation.org. Pre-history lives into the present.

Getting the lay of Division St.

East Falls NOW, February 2023, by Caroline Slama

Head 495 feet up a certain twenty-foot wide street leading northeastward from Conrad Street, and you might lose your bearings. That was how I felt tracing the history of Division Street, the dead-end right-of-way that runs between and parallel to Bowman Street and Sunnyside Avenue. My questions were simple: Why the dead end? Why the grade changes? And why the name? As I gathered evidence and retraced my steps, the collections of the East Falls Historical Society were key to making sense of the facts and placing them in context. Documents from various city archives helped as well.

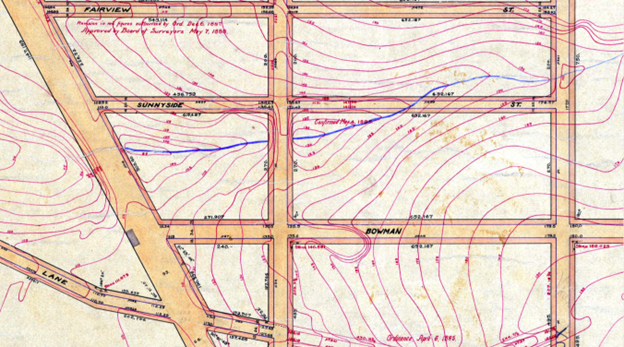

Research began with the Streets Department’s digitized legal cards, which showed that Division Street was opened by affidavit in October 1911 and added to the city plan in March 1912. The Department’s Bureau of Surveys provided scans of the street’s plan and of the affidavits, in which three Falls residents (PDF, 2 Meg)averred that Division Street had been in continuous use since 1876. The city staff also shared a digitized copy of an 1875 topographic plan of the area. Division Street is absent, but Ainslie (Fairview), Sunnyside, and Bowman Streets appear— along with a stream flowing from a point above Vaux Street, across the bed of Sunnyside on the block where Division Street would come to be, and continuing down to the railroad. The historic watercourse— and the need to fill it in as lots were laid out—may partly explain the dramatic grade changes on Division Street and neighboring blocks.

Property records also help explain why the street comes to a dead end at a line that veers off at an angle to the rest of the street grid. Property maps and deeds show that this line is the remnant of the southwestern boundary of a large tract that once fronted on Indian Queen Lane and that was occupied by the Garrett family from the early 1700s to the 1920s. Property descriptions recorded in the 1880s for lots at the end of Division Street refer to “the line of Garrett’s land,” wording that persists in boundary descriptions in some recent deeds.

In a series of sheriff sales in the late 1860s and early 1870s, the property southwest of the line of Garrett’s land and surrounding what would become Division Street passed from businessman and politician Charles F. Abbot to his brother-in-law, physician Horace Evans. After selling off some of the irregular lots bordering the Garrett land, Evans conveyed the bulk of the block to his nephews Griffith Evans Abbot and Horace Evans Richards in the early 1880s.

Who were these cousins? The EFHS collection of scrapbooks by local newspaperman Alexander Cox Chadwick, Jr. (1890-1957), available as searchable PDFson the EFHS website, provided details unlikely to be found anywhere else. Volumes 31 (PDF, 23 Meg) and 32(PDF, 26 Meg) contain letters from reporter Robert Roberts Shronk (1844-1921), whose candid recollections as a contemporary paint a picture of Horace Evans Richards and Griffith Evans Abbot as profligates and ne’er-do-wells, with tenuous connections to the Falls. In a 1920 letter, Shronk recalls, “When Dr. Evans gave Griffith Abbott and Horace Richards the last fronting on Queen Lane, Grif, according to his Uncle showed great enterprise by erecting a row of dwellings on Sunnyside avenue. He lost the row and the property. […] The last heard of Grif was when he was clerking in a Boston book store.” Indeed, the 1920 census finds Griffith Evans Abbot rooming in Boston and working as a proofreader for a book company; he would die at a retirement home for physicians in western New York in 1927.

And as for the origin of the street name? A “list of Streets, Thirty Feet wide and under, now Built upon, but not on the City Plan” compiled in 1890 by the Bureau of Surveys, plus a liquor license application (PDF, 1 Meg)from 1892 for 3432 Division, show that the name was in widespread use by the early 1890s. Perhaps the street name was a generic placeholder on a subdivision plan, or perhaps the name reflects the division between Horace Evans Richards’ property interests fronting on Bowman, and Griffith Evans Abbot’s interests on Sunnyside. Registry records for a lot between the south side of Sunnyside Avenue to Division refer to the parcel as “Being Lot No. 3 on a certain plan of this and other ground of Griffith Evans Abbott.” Other registry records describe the street as being laid out for the mutual use and benefit of properties on Sunnyside.

Far from leading to a dead-end, the process of researching this narrow, one-block right-of-way has opened up other avenues of inquiry and shown the unique research value of East Falls Historical Society’s archival collections.

The Forgotten Kelly: Grace’s Uncle George

East Falls NOW, March 2023, by Richard Lampert

Almost everyone in East Falls knows something about the Kelly family, arguably our community’s most prominent family for much of the 20th century – at least about Grace Kelly, the Academy-Award winning actress who became Princess of Monaco.

As glittering as Grace Kelly’s show-business career was, she wasn’t the first Kelly in show business and, by some lights, perhaps not even the most successful. George Kelly, her uncle, won a Pulitzer Prize in drama for his third play on Broadway, Craig’s Wife, in 1926. Kelly’s first play, The Torch-Bearer, opened on Broadway in 1922, and his last script, a forgettable TV play called The Fatal Weakness, ran in 1976 – two years after his death. So George Kelly’s playwrighting career ran for 54 years, with nearly three dozen credits across stage, screen, and television.

George Kelly’s most successful play was his second, The Show-Off, which premiered in 1924 and ran for about 15 months. According to the International Broadway Data Base (IBDB), it also had six revival runs, most recently for about six weeks in 1992, and was the basis for four movies. In reference sources, this is described as a comedy, although 21st-century audiences probably wouldn’t be laughing out loud.

Just four months after The Show-Off closed, Craig’s Wife opened, running for about 10 months. According to IBDB, it was revived only once – for two months in 1947 – and it’s the basis for three Hollywood movies. The published version of the play carries the subtitle A Drama, and reference sources invariably agree with the description.

The published versions of these two plays also contain a notice that Kelly himself controls “stage, screen, and amateur rights” to performances of the play. Although he was an active participant in Broadway, Kelly clearly maintained his ties to East Falls: The notice about performance rights shows his contact address as 3665 Midvale Avenue. Based on the 1920 census, this seems to have been his parents’ home at the time. (It was near the small convent next to St. Bridget Church. Later in life he lived in nearby Germantown, possibly at Alden Park.)

Kelly continued to write for the stage following Craig’s Wife, but his subsequent plays took an increasingly dark and judgmental turn, and they failed to attract large audiences. A contemporary critic wrote of his plays, “Kelly appears to be anti-love, anti-romantic love, and distrustful of the tender emotions.” As Broadway audiences turned away, leaving four of Kelly’s scripts unproduced, Kelly began to write for the movies and the many television drama series that were popular after World War II.

Despite the fact that Kelly began his career writing and performing in vaudeville sketches as far back as 1912, apparently he was not a light-hearted man.

An unsigned profile of Kelly that ran in the Brooklyn Eagle not long after the successful premier of Craig’s Wife had this to say about him: “He is a shy man by nature and retiring – so retiring, in fact, that on three occasions, when he could have come before enthusiastic audiences at the premier of ‘The Torch Bearers’, ‘The Show-Off’, and latterly at ‘Craig’s Wife’ to accept their applause, he ran away to far away dressing room nooks, locking the door behind him.”

It is possible that Kelly’s sexual orientation had something to do with the very private life he led. During his career, he was known as a lifelong bachelor, and for 55 years he lived and traveled with a man named William Eldon Weagley, who was described as Kelly’s “valet.” According to some accounts, Weagley was not invited to Kelly’s funeral, held in 1974 in Bryn Mawr, so he slipped into a back pew and witnessed the service anonymously.

A digital walking tour of the East Falls Historical Society website

East Falls NOW, April 2023, by Richard Lampert

[The links have been updated to the new (Sept. 2023) website]

A couple of months ago, a column by our board member Caroline Slama delved into the history of tiny Division Street. Caroline’s research, as she pointed out, included some dives into our website – https://eastfallshistoricalsociety.org. Caroline’s research touched on just a small part of the historical information on our website, a product of two decades of work. As you’ll see, our webmaster Roger Marsh has worked heroically to accommodate a vast quantity of materials that started in many different formats.

Clicking on the Explore link in our menu is the way to start. The menu items lead to a wide range of materials, and we cover some of the highlights in the rest of this column.

Oral histories: There are 55 of these on our site, with more being added on a regular basis. Over the last 20 years, EFHS volunteers have interviewed longtime Fallsers from everyday folk to luminaries, and the interviews are transcribed in their entirety. These transcripts offer fascinating insights into life in East Falls, with recollections covering most of the 20th century. The emphasis is on day-to-day life – shopping, church, school, and recreation – and collectively they paint a vivid picture of a tight, proud community. Look on the menu for Oral Histories. There is an index, as well as browse-able pictures.

The ”Blue Book”: Longtime Fallsers recall the 1976 publication, East Falls – 300 Years of History, a densely packed 80-page book produced by a team of volunteers headed by Lois and Fred Childs as a Bicentennial project. The print run sold out long ago, and anyone who’s looking for a copy might find one at one of our library books sales or a flea market somewhere. For those who can’t find a hardcopy, our website has the whole thing in digital form – and it’s searchable. For many people, it’s the foundational source of knowledge about East Falls. You can find this on the menu bar by clicking on Resources.

Chadwick Papers: This resource, complied by a local newspaper publisher named Alexander Cox Chadwick, was one of the prime sources for the authors of the Blue Book. It’s filled with granular items – mainly newspaper clippings, but also church programs, some transit schedules, and letters. While the bulk of the materials were compiled between 1900 and 1937, there are scattered items dealing with the late 19th Century as well. We have digitized most of the 37 volumes of scrapbooks. There’s a Chadwick Papers heading under Resources. We developed a simple subject index, and it’s also possible to search within a given volume.

Early History of the Falls of Schuylkill: This 102-page book, originally published in 1869, was written by a historian named Charles V. Hagner, and it was another of the key sources for the Blue Book. Hagner’s book starts with the Lenape Native Americans and goes on from there, covering history along the Schuylkill from Manayunk down to the Fairmount Water Works. Our website offers the entire book in digital form, and it’s searchable. On the menu, click on Resources – you’ll see a link to this work next to the link to the Blue Book.

Photos: Our website provides a modest collection. Arguably, the highlight is the sequence of 23 photographs covering the construction and initial appearance of the Falls of Schuylkill Library. There’s a Photos item under Explore.

Historic sites: Did you know there are 24 sites in East Falls that are listed on the national or Philadelphia register of historic places, or have a Pennsylvania Museum and Historic Society marker? This part of the EFHS website provides a map showing all the locations, along with brief commentary and links to detailed documentation. Just click on Historic Sites.

The “Daisy Quilt”: This artifact, which East Falls Historical Society acquired in 2020, provides a detailed look into the membership of the Methodist Episcopal Church of East Falls in the late 1890’s, with over 600 names embroidered in the segments of the quilt. Hours of work by our members Patty Cheek, Ellen Sheehan, and Joe Terry deciphered most of the names, which provide tantalizing glimpses of family names that persist into the present in East Falls. The website provides a couple of different tools for people who want to explore this fragile artifact. To see for yourself, click on Daisy Quilt.

EFHS starts development of an online encyclopedia of East Falls history

East Falls NOW, May 2023, by Richard Lampert and Steven Peitzman

Back in 1976, a group of volunteers led by Lois and Fred Childs created a densely packed 80-page book called East Falls: 300 Years of History, coordinating with a host of local efforts around the Bicentennial. It’s come to be known, with great respect, as The Blue Book. With 2026 approaching – the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and the 50th anniversary of The Blue Book – East Falls Historical Society is hoping to follow in the footsteps of the earlier effort.

Among the most seismic changes of the last 50 years has been the development of the Internet, and for that reason EFHS is going to focus on building a constantly evolving online “encyclopedia” of East Falls history. We envision that this will grow over many years. Eventually, we hope, this will be a comprehensive, searchable resource covering the people, places, events, and geography that have made East Falls what it is.

This resource will live alongside the abundant resources that are currently available on our website – the Blue Book, the Chadwick Papers, and many others. This new resource will offer a fresh approach designed for digital access, viewing East Falls history from the days of the Lenape and the earliest European settlers up to the present.

To demonstrate the breadth of our ambitions, the EFHS Board has determined that the following topics are the “Top 10” topics to cover as part of our initial release, in alphabetical order:

- Architecture overview (to include Tudor-style, Queen Lane Manor, row houses, etc.)

- Churches

- Dobson Mills

- Falls Bridge

- Falls of Schuylkill Library

- Kelly Family

- Old Academy (the building and the theater company)

- Powers & Weightman (to include subsequent development of Laboratory Hill)

- Railroads (freight and passenger)/bridges/public transport

- Woman’s Medical College (to include Medical College of Pennsylvania)

Why are we alerting East Falls to this project three years ahead of the target date? Because this is a huge undertaking, and we need help. We’re looking for writers, as well as people to uncover relevant photos and graphics. If you have a keen interest or special knowledge about one of our “Top 10” topics or another interesting facet of East Falls history, tell us what you’d like to work on, and we’ll provide some guidance. We’ve developed sample writeups and other helpful aids for writers and will be happy to share them.

This will be a multi-year venture. Stay tuned for updates!

Ridge Ave.: History and architecture

East Falls NOW, June 2023, by Nancy Pontone

New developments are hemming in blocks of historic buildings on Ridge Avenue in East Falls. Developers have taken advantage of zoning which allows 4-story buildings by right. Let’s take a look at buildings on the 4000, 4100 and 4200 blocks of Ridge Avenue to understand what they tell us about East Falls history.

East Falls was a Lenape fishing settlement before colonization. Welsh men from Philadelphia built a fishing clubhouse near the falls in 1755. Fishing plus the lively waterfalls and scenery led to a fishing industry and tourism. Inns were built to accommodate travelers, while mills for paper and grist utilized the flowing waters. All the buildings from this period in the 18th century are gone. The last demolished was the lamented Falls Tavern in 1971.

The 19th century ushered in a new industrial era when the railroad arrived in 1834 and the Dobson textile mills in 1855. Housing and retail were needed for the thousands of mill workers.

Across Ridge Avenue from Dobson Mills on the 4000 block, Sarah M. Dickson and her husband, developed twenty-three 3-story buildings replacing an inn located near Bridge St. Groups of four and up to six buildings share design features but all are mixed-use (commercial and residential) brick buildings built between c 1876 and 1883. Four of the 23 buildings have been demolished. Occupants were primarily mill workers such as blanket finishers, weavers, dyers, loom fixers and warp dressers. Since retail occupied the first floors, a barber, grocer, liquor store keeper, jeweler, and milliner who lived here presumably resided above their stores.

Moving up to the 4100 block, three structures (4133-4137) of nineteen built in the 1860s remain after demolition for the Route 1 overpass. In 1870 John Dobson purchased land plus the nineteen 3-story brick buildings. These housed mill workers but also a dry goods merchant and his store in 4137. The next twelve mixed-use buildings (4141-4163) dating from 1896 were built by owner John Dobson on the purchased land. Presumably Dobson quarried this area because the foundations were built from stone taken from the cellars. In 1934, six of these 3-story structures (4149-4159) were converted to residential only and reduced to 2-stories. First floor retail space has been modified. Again, many occupants were mill workers.

The next six residences (4165-4175) with mansard roofs are on the site of the former Smith family stables and wagon works. John Dobson purchased this land in 1886 plus the Falls Tavern and vacant land across the street. The six brick houses were not built until after 1900. The end unit housed a doctor and his family. Across the street (4144-4152), five single family 3-story residences of buff brick with large Roman style porch arches were built adjacent to the Tavern, under John Dobson’s ownership, but again not until after 1900. Many of the residents were mill workers.

Further up Ridge Avenue is a mixed-use classical revival building (4189) from 1913 on the corner of Indian Queen Lane and on the opposite corner (4201) is a mid-19th century building shown in historic photos as a pharmacy with an overhanging cornice. Next door (4203), John Hohenadel, a local brewer, built a classical revival mixed-use establishment with five parts fronting on Midvale Avenue. This building’s centennial is in 2023. “Majors” (4207) across the street is an Italianate mixed-use building from the mid-19th century. Further up, William Albrecht, another Falls builder, constructed a block of five Italianate mixed-use 3-story brick buildings (4215-4223) c 1896. Albrecht also built a 2-story brick commercial building and hall (4225-4233) with an overhanging cornice across Eveline St c 1899. Next are five Second Empire/Queen Anne style mixed-use 3-story brick buildings (4235-4243) constructed by Henry J. Becker, builder, c 1891-1892, the most ornate buildings on Ridge Avenue. Becker also built Palestine Hall at 4200-4206 Ridge Avenue in 1868, a property on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. More mid-19th century Italianate and Greek Revival buildings line the east side of Ridge Avenue. 4253 stands out as an Italianate building with ornate brickwork not unlike that found on the 4000 block. It was built by owner John Dobson c 1884-85 and became a clinic for The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in the late 1920s.

These buildings tell stories of East Falls history and stand as testaments to solid construction, natural materials and authentic design.

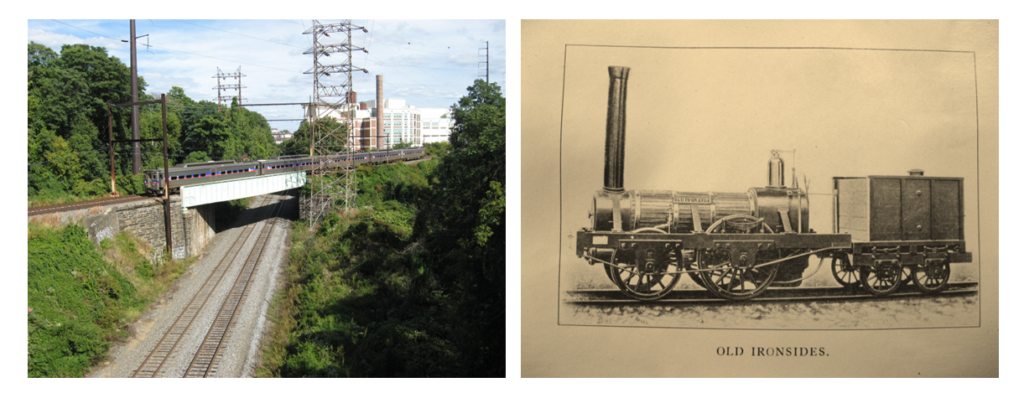

Right: “Old Ironsides,” the first locomotive built by Mathias Baldwin, and the first bought by the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad

East Falls played an historic role in development of early rail lines

East Falls NOW, July 2023, by Steven J. Peitzman

At the far eastern reach of East Falls–and visible only by peaking over the east parapet of the Henry Avenue Bridge south of the A. Philip Randolph school–two historic rail lines cross. Tracks passing above carry the familiar trains of the SEPTA Norristown line, once the Norristown Branch of the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad, chartered in 1831. Belowlies the former Richmond branch of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, chartered in 1833; these rails are now part of the vast CSX system. The P G & N and the P & R count as two of the earliest and most historic rail lines in Pennsylvania. Though neither was built with Falls of Schuylkill (East Falls) in mind, they enabled our town to thrive from the 1850s well into the twentieth century.

Several Germantowners initiated the P G & N to connect Philadelphia to Germantown, a separate and growing municipality in the 1830s. To amplify its use and gain support, they envisioned continuing west from Germantown to Norristown, though the obstacles in such a route placed this branch to the south, the current configuration. The Norristown Branch opened to Manayunk in 1834, and to the final destination in 1835. We presume there was a stop, though no station building at first, at the Falls. Later maps show the station near Indian Queen Lane. Another station stood at School House Lane, where Wissahickon Brewery is now. South of School House Lane at the west extreme of East Falls the chemical works of Powers and Weightman arose in the 1850s, to become a massive complex. Atlases from 1875 and 1895 show the factory served by multiple sidings coming off the P G & N, no doubt used to bring in raw materials and ship out the final chemical products

The first P G & N locomotive was “Ironsides,” the first steam engine built by Philadelphian Matthias Baldwin, whose company became the industry’s leader. Early on, horses pulled some trains.

In 1870, the P G & N was leased for 999 years by the aggressively expanding Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. Chartered in 1833, it ran its first train in 1842. Though it did, of course, connect its named cities, the line’s real purpose was to haul anthracite coal from Schuylkill County mines to Philadelphia, and beyond by rail or water. It ran along the Schuylkill to a junction at West Falls; the main line continued to the city, the other crossed the river into Falls of Schuylkill (East Falls), then looped across town to wharves on the Delaware, at Port Richmond. But this line, the Richmond Branch, was also well-situated to haul enormous loads of wool to the mills of John and James Dobson, which began operations in the Falls in 1856. According to one account, the Dobsons’ plant received over 3000 tons annually by the 1870s. As the mills transitioned from water power to steam, the P & R also delivered the needed coal, possibly high-energy anthracite directly from the mines. And the Reading carried the famous Dobson blankets and carpets outbound to the world. The growth of the Dobsons’ complex, the single largest textile business in Philadelphia, and the livelihood of its 6000 workers (at peak) depended upon the P & R. And our town very much depended upon the Dobsons. Some of us live and shop in structures built by John Dobson over 100 years ago.

A more complete story of the railroads to and through East Falls, including the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Chestnut Hill line (now the Chestnut Hill West line, stopping at Queen Lane), will be the subject of a future EFHS illustrated lecture.

Family, Dobson Mills, and baseball: An East Falls saga. Part One

East Falls NOW, August 2023, by Mike Ousey and Rich Lampert

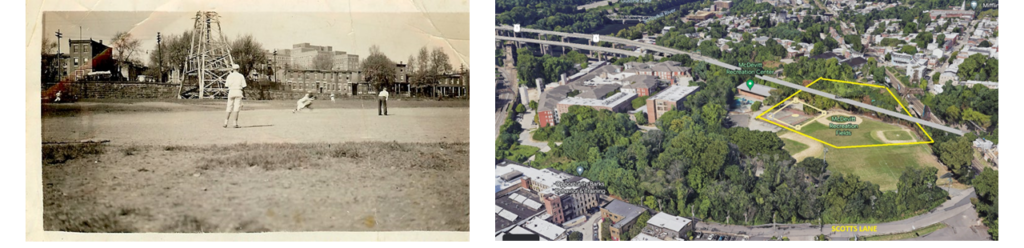

Right: Note the bulky building of Woman’s Medical College in the background – a building that did not exist until 1929-1930. (Courtesy of Mike Ousey)

Scattered in our community and the broader Philadelphia region live descendants of past Fallsers who worked at Dobson Mills (not its formal business name, but it’s the name we all use.) After all, at its peak, the complex employed some 6000 workers! Mike Ousey, now living in Mount Airy, is one of these descendants. His third great-grandfather, Joseph Ousey, hailed from the same village in England as John and James Dobson and was intimately familiar with the workings of English mills. According to Ousey family lore, Joseph Ousey was recruited by the Dobson brothers to be a supervisor at Dobson Mills.

Another element of East Falls history, which Rich wrote about in this space in 2020, is an enduring link to baseball. Thanks to Mike’s family history and research, for this month’s and next month’s issues of East Falls NOW, we’ll knit together family, Dobson Mills, and baseball.

The Ousey family fell hard for baseball, according to Mike. Presumably his ancestor Joseph was familiar with other British games involving a bat and ball. In mid-19th century America, baseball wasn’t quite the sport we know today; it was still a high-scoring game of inconsistent length. It wasn’t until the 1870s that amateur teams routinely pitched overhand, wore gloves, and called balls and strikes. After these rule changes, baseball became a lower scoring, more intense, and shorter game – just the kind of activity young men could fit into a weekend after a long week of work at the mill.

One of the teams that played this more exciting and modern style of ball was called the “Lakerim Athletic Club,” named for a popular boy’s adventure book published in 1898. This was a team that Joseph Ousey’s grandson Bill played for. The club apparently started in 1898 and existed through 1910 or so.

As the game increasingly captured the working class’s attention, the barons of industry began to take notice. During the 1910’s, many companies were sponsoring baseball teams. Dobson Mills was one of them, and it wasn’t even the only one from East Falls. An article in the Philadelphia Inquirer from 1915 reported that Powers-Weightman-Rosengarten, the chemical manufacturer located on the hill rising from modern-day Ridge Avenue and Merrick Road, had organized a team. Apparently the Industrial League of Philadelphia couldn’t offer the company a slot; so, the article stated, they were looking for a comparable league to join.

As we’ll discuss in more detail in next month’s column, Dobson Mills really dug into baseball in 1917, creating one of the best semi-pro baseball fields in the city as well as incorporating a formal business entity related to their company baseball team. The field outlived the company: Dobson Mills went out of business in 1927, but games were still being played on the field into the late 1930’s or beyond. A photo in Mike Ousey’s possession shows a game underway at Dobson Field, and in the background is a clear view of Woman’s Medical College, which opened in 1930. Also, a small article in the Inquirer from 1939 mentions a team called “East Falls” playing at Dobson Field.

While many of the buildings of Dobson Mills survive today in the Dobson Mills and Sherman Mills complexes, the Dobson baseball field is no more. A deep excavation for the Roosevelt Boulevard extension cut straight across the middle of the field. The remaining northern segment constitutes much of McDevitt Recreation Center, while the southern remnant is a scrubby woodland.

September

Dobson Mills: A Great Name In Woolens – And Baseball, Too

East Falls NOW, September 2023, by Mike Ousey and Rich Lampert

As we were drafting this article, the Phillies were competing for a wild card slot in the MLB playoffs. By the time this article appears–who knows? We hope this piece reinforces everyone’s interest in baseball. But in case the Phillies have fallen out of contention, it can serve as a reminder of happier days on Philadelphia diamonds.

As we recounted in last month’s NOW, the Ousey family has longstanding ties to John and James Dobson, the owners of Dobson Mills, dating back to the 1850’s. Also, the Ousey family has shown an enduring love of baseball. This month’s installment focuses on Dobson Mills as a powerhouse in semi-pro baseball.

This part of the story begins in 1917. During that year, the company organized the John and James Dobson, Inc., Athletic Association. The honorary president was James Dobson, and his daughter Bessie (“Mrs. B. Dobson Altemus”) was listed as one of three honorary vice presidents. This was serious business: The Philadelphia Public Ledger reported that the team was planning to build “one of the best diamonds in the vicinity,” including a grandstand that would seat 600. Did Bessie Dobson, the honorary vice president, take in any games? She could have: the location of the field, part of which is now the McDevitt Recreation Center, was an easy five-minute walk from her family home, the mansion Bella Vista, now the site of Abbottsford Homes. The Dobson team was in the northern division of the (Philadelphia) Industrial League, which played on Saturdays from late April to mid-September, with a post-season on the following three Saturdays. In addition to spending generously on the playing field, the Dobson team apparently didn’t stint on recruiting players – its starting pitcher and catcher were reportedly poached from the 1915 Industrial League championship team, that of Hale & Kilburn, a major manufacturer of railroad components.

By 1920, Dobson Mills was playing in the so-called Philadelphia League, with a couple of intriguing opponents. One was Pencoyd Steel, just across the river in Bala. The other was even more intriguing – the Hilldale Daisies, from Darby. (Really, a baseball team called the Daisies?) The Daisies were a Negro League team. In 1921, not only did Dobson play against Hilldale during the regular season, the two teams also played a sort of “world series” after the Dobson lads won the Industrial League championship. In 1922, Dobson Mills played three games in three days against Hilldale – one in Camden, one in Darby, and the final one on their home field. This may have been an exhibition series, generating some funds for the teams. Dobson Mills won the Philadelphia League championship again in 1923, although the league apparently was on its last legs (as were the mills). By the time the Dobson team entered its powerhouse days, Mike’s ancestor Bill Ousey was married and settled; and his son Jack was too young to play, but the family certainly would have been watching. As the photo attests, the family has maintained its links to amateur baseball in the years since – a heritage founded here in our community.

The Dobson business closed in 1927. However, as we noted in last month’s article, the field continued in use at least through the late 1930’s.

Family, Dobson Mills, and baseball – does it get any more East Falls than that?

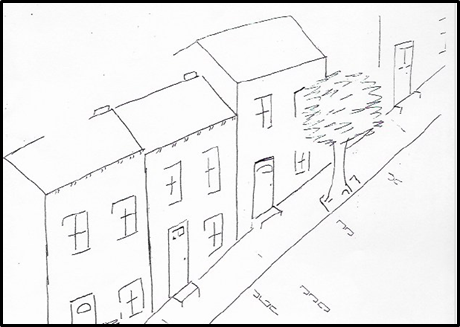

East Falls in the 1930‘s — a newly discovered series of visual memories in a whimsical and different way of recording history

East Falls NOW, October 2023. Drawings by by Gilda Coyne, annotation by Rich Lampert

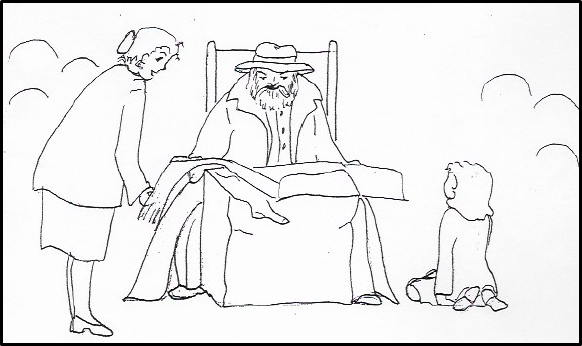

History is recorded in many ways. The website of East Falls Historical Society (eastfallshistoricalsociety.org) includes modalities such as the Chadwick Papers, a compilation of thousands of newspaper clippings and ephemera; a scholarly historical work written in the 19th century; information about historic sites in the community; historical photographs; and our unique collection of oral histories. This month, we take a new look at history, through drawings created by a Fallser who remembered growing up here in the decade-plus before World War II.

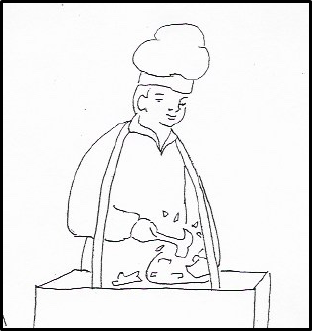

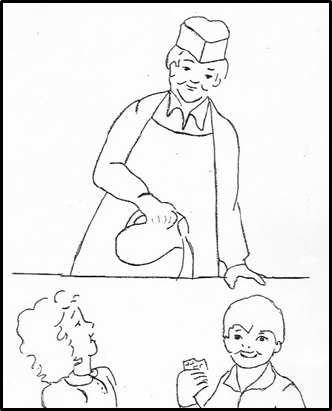

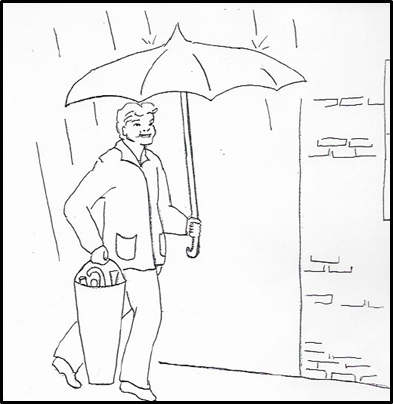

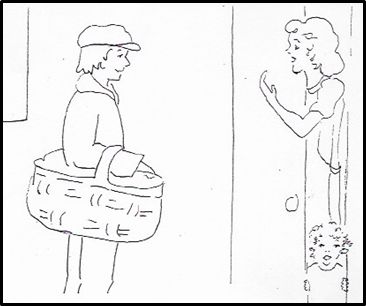

The artist is Gilda Coyne, who grew up in the Ierardi family on Calumet Street, where they owned a grocery store. In the mid-1950’s, she wrote a handful of brief stories, mostly for her grandchildren, based on her girlhood. While her stories don’t mention East Falls specifically, they fit nicely with what we learned in interviewing her younger sister, Inez Ierardi Fletcher, for our oral history series. Gilda was in her late 50’s and had moved from East Falls decades earlier when she created her stories, but the associated drawings capture the innocence of her childhood in this community.

One of Gilda’s stories, called “Tuesday John,” describes the many peddlers who visited Calumet Street in the 1930’s. It provides some fascinating insights into daily life through a child’s eyes.

Gilda Coyne had hoped to get a couple of her stories published shortly after she wrote them, but she wasn’t successful. In hindsight, we think some editors may have missed an opportunity.

We’re grateful to Gilda Coyne’s niece, Judy Fletcher, who currently lives in Havertown but recalls her East Falls roots fondly, for letting us see her aunt’s stories – more facets of the East Falls community we appreciate, in a form we hadn’t seen before.

110 years old — origins and architecture of Falls of Schuylkill Library

(original title: “The Falls Of Schuylkill Branch Of The FLP: Origins And Architecture”)

East Falls NOW, November 2023, by Ellen S. Prantil-Bartlett

The Falls of Schuylkill Library at Warden Drive and Midvale Avenue celebrates its 110th birthday this month! Let’s recall how our library came to be, and also appreciate its architectural distinction.

As the 1840s approached, the Falls of Schuylkill, or Falls Village, was a going concern. Though its decades as a major industrial site would begin in the 1850s (the Dobson Mills, the Powers and Weightman chemical works), the river town with its few small mills, fishing industry, and its tourist activity were served by a new railroad and ferries. The Academy on Indian Queen Lane (not yet “Old”) housed education and worship. But some Fallsers wanted a library.

In February 1844, they formed “Schuylkill Falls Library Association,” with membership by subscription. This is our first known library: part of its original ledger, indicating dues and fines paid (in calligraphy), was donated to the EFHS in 2021, a small but treasured document.

The second library in East Falls – the “Falls of Schuylkill Free Library” opened June 6, 1901 on the second floor of the Old Academy. Requiring no dues, it operated under the auspices of the Free Library of Philadelphia, which provided the books. But it was largely maintained by local philanthropists, mainly William Weightman of Powers & Weightman, who outfitted the space and paid the librarian’s salary.

Our current library was built through major funding from Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie, a businessman and philanthropist, constructed 2,509 libraries worldwide, of which 25 were in Philadelphia (18 remain in operation). His mission was to provide the space for all who desired to be enlightened, while the locality (e.g., Philadelphia) would provide the books. Carnegie required a financial commitment for the maintenance and operation of the library from the town that received the donation. This would insure local public support. To this end, the building site was donated by the William G. Warden estate (Standard Oil Company) and William Merrick, Esq.

Now and for many years, the city of Philadelphia buys the book, pays salaries, and maintains the building (along with the Friends of Falls Library, established in 1987).

In 1912, ground was broken for the current building. Architects Rankin, Kellogg & Crane used a formal English Collegiate Gothic aesthetic in Wissahickon schist, to complement the nearby houses and church. The formal entrance staircase, typical of Carnegie libraries, is raised from the street as a symbol of rising to the enlightenment of learning. Much of the Gothic style shows in the entrance; refer to the photo, or even better, take a careful look when you are next at the library. The Gothic elements include: the compound pointed Tudor arch; the parapet (small stone wall capping the entrance) with crenels (the indentations, originally for shooting arrows); the quadrafoil ornaments; and the buttresses. Note also the two open books in the stonework flanking “THE FREE LIBRARY OF PHILADELPHIA” – this is, after all, a library, not a castle. The building’s windows with small panes and heavy stone framing also typify the Collegiate Gothic style.

The grand interior is rectangular with arched ceiling and exposed beams.

The library opened on November 18, 1913 with a festive celebration. In the 1950s it was renovated, moving the circulation desk to the right of the entrance. In 1997 another renovation returned to the original design with a central circulation desk. It is the library we know today.

Wendy Moody, former Branch Manner of the library, and Steven J. Peitzman, contributed to this article. Do you have questions about East Falls history, or want to know more? See our growing website at eastfallshistoricalsociety.org, or contact us at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. And join! You can do so on our website.

John Dobson built a legacy in East Falls – with his mills and real estate

East Falls NOW, December 2023, by Nancy Pontone and Steven Peitzman

Born in 1827, John Dobson worked as a child in cotton mills near Manchester England, emigrated to the US around 1850, and built and managed the largest woolen goods complex in Philadelphia here in Falls of Schuylkill (now East Falls). He first found work with Joseph Schofield’s local mill and married a Schofield daughter. In 1856, after a fire destroyed a mill Dobson opened in Manayunk, he started one in the Falls where the 18th century era of fishing, tourism, and water-powered mills ended with the 1821 Schuylkill River damming that submerged the falls.

Though relatively new in the Philadelphia textile arena, John Dobson succeeded in obtaining one of the largest contracts to manufacture woolen blankets for the Union Army during the Civil War. Throughout the conflict, the demand for blankets grew, and the company enjoyed large profits. Twice during the war, John Dobson left the mills to lead a unit of Pennsylvania Volunteers (the “Blue Reserves”) including many of his workers, into service. Dobson continued to pay soldiers’ wives, while Mrs. Dobson looked after the business. Dobson bought out two partners and took on his brother James as an associate during or soon after the Civil War.

The Dobson brothers’ story was one of rapid growth: additions to expand carpet-making and the hiring of hundreds of skilled workers, many English and Irish immigrants. New buildings, made from Wissahickon schist excavated on site, arose in 1862 through 1873 and beyond. Steam engines powered production of cloth, blankets, and carpets; this consumed 20,000 pounds of wool daily and 600,000 pounds of cotton warps annually. The Dobsons sold their carpets at their 809-811 Chestnut Street showrooms, and through agents in New York and beyond.

At its peak, the Dobson Mills employed an estimated 6,000 workers. John, the founder, made an enormous amount of money (as did his brother), and became a major land-holder in the neighborhood. Near the mills Dobson developed dwellings under his own name to rent to mill workers and others as the community grew. An inventory of the John Dobson estate showed real estate holdings throughout Philadelphia and its suburbs, and as far away as Kentucky and Texas.

Both brothers lived in Falls of Schuylkill and practiced a hands-on management style, called “fraternal paternalism.” Although they paid good wages, relations between the brothers and their workers crumbled in the economically disastrous 1890s, resulting in discord and strikes. In January 1891, the carpet mill, west of Scott’s Lane, suffered a spectacular fire. Rebuilding followed, and carpet production resumed in less than a year. The Philadelphia textile industry, however, entered a period of decline in the 1920s. John and James Dobson Carpet Mills went out of business in 1927, a victim of national “brand name” products. John Dobson had died in 1911, and James in 1926. Neither had sons, and no family member had the interest or capability to confront the challenges.

Surviving mill buildings are on the National Register of Historic Places and were deemed eligible for the Philadelphia Register although not ultimately protected.

A recent East Falls Historical Society walking tour pointed out the following extant buildings or sites developed by John Dobson:

- 4165-75 Ridge Ave – Six 3-story Second Empire style row houses, built c 1901-1906

- 4144-4152 Ridge Ave – Five 3-story row houses with Classical style arches, built c 1901-1911

- 4141-4163 Ridge Ave – Twelve 3-story mixed use row houses with 2-story bays, c 1896, built by Charles E. Bartle; six were reduced to 2-stories in 1934.

- Several mill buildings seen west of Scotts Lane, including the last mill building added, in 1915, now in residential re-use (part of “Dobson Mills,” formerly “Chelsea”); it and two early buildings will soon be hidden behind new construction.

- Various mill buildings east of Scotts Lane (“Sherman Mills,” “Scotts Mills”), residential and other reuse)

- 3231-3239 Sugden’s Row (formerly Dobson’s Row) with four remaining row houses, once with units front and back, c 1860s-1870s.

- 3401-3443 W Westmoreland Street row houses, 1870s.

- 3414-16, 3418-20 & 3422-24 W Westmoreland Street. originally four-unit residences, 1890-91

- 3429 Allegheny Ave – The gate house of John Dobson’s estate, built c 1900; the main house, which was near present 34th and Allegheny, does not survive.