With leaves down, now’s the best time to see French and Spanish styles in EF

East Falls NOW, January 2022, by Steven J. Peitzman

Last September’s EFHS article in the NOW reviewed the Tudor Revival and Italianate styles, prevalent in the Falls. Here is some refresher. The Italianate style as seen in countless row houses west of Henry Avenue is marked by a prominent cornice with brackets, and sometimes narrow, tall windows with rounded window hoods. The Tudor, or old English appearance, shows (faux) “half-timbering” (wood strips over stucco), peaked gables, sometimes pointed arches, grouped windows.

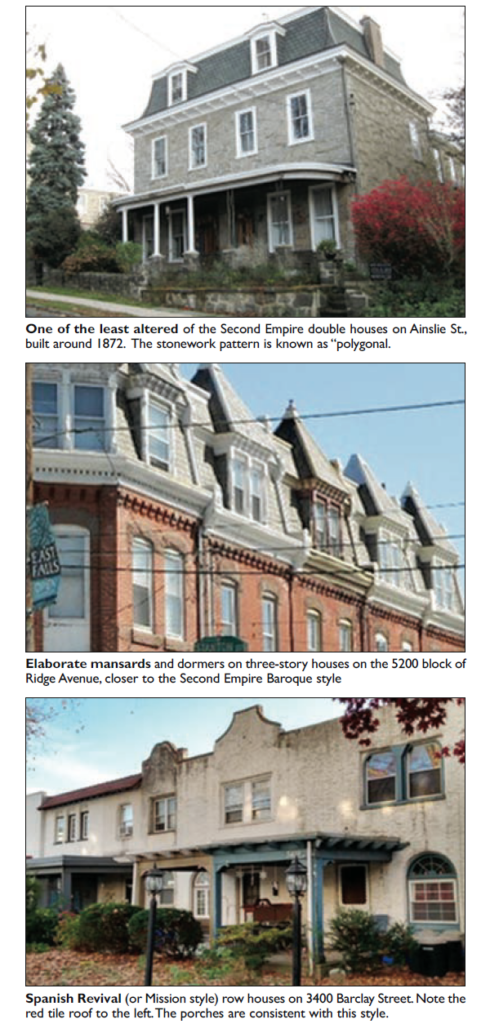

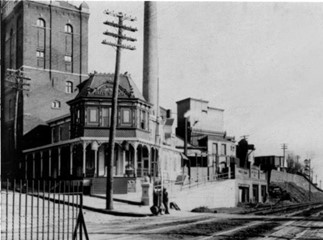

This month, we leave Italy and Britain to discuss a style imported from France, and another from Spain, though filtered through California and the Southwest. The rebuilding of Paris in the 1850s and 1860s under Napoleon III, and the expansion of the Louvre, influenced architecture in Europe and North America. The Second Empire look took hold for grand buildings down to modest houses, and did so in the United States beginning mostly in the 1860s. The essential feature is the mansard roof, with steeply slanted and often rounded (concave or convex) sections visible from the street. Almost always, these contain dormer windows. Below the mansards of a house, the cornice is often of the Italianate style. The mansard roof provides more usable attic space than a simple slanted gabled type. In its florid form, the Second Empire Baroque, we see columns, statues, balconies and all manner of classical ornament: a grandiose examples is our Philadelphia City Hall. Figure 1 is one of the better preserved of the remarkable ten Second Empire double houses, built c. 1872, which in effect formed the unique Ainslie (formerly Fairview) Street. Figure 2 shows the ornate mansards and dormers with Italianate styling below, in the 4200 block of Ridge Avenue.

Out of San Diego and the Panama California Exhibition of 1915 came a taste for the Spanish, or Mission, look. The clues for the architecture spotter include: red tile roof; curvilinear gables or parapets (ornamental upward extensions of the front wall), arched window openings, stucco or plaster walls sometimes with inserted tiles. The Spanish/Mission motif reached a point of near mania by 1925, which is exactly when it reached East Falls and apparently the eye of developer M. J. McCrudden. We may have more Spanish style rows per acre than any neighborhood in the city. Figure 3 shows some typical examples on Barclay Street, but readers also should explore the 3400 block of Vaux Street, Osmond Street, and the wonderful small row on Conrad next to the Thomas Mifflin School. In fact, all Fallsers should go out in the winter, with or without your dogs, to just look at our varied built environment – you see more with the trees bare. Then think about how covering cornices with siding, making round-headed windows square, removing red tile roofing, and the like, diminish the charm and distinction of our neighborhood.

Yes, George Washington did sleep here

East Falls NOW, March 2022, by Rich Lampert

Although President’s Day has come and gone, it’s always a good time to revisit East Falls as a site of action during the Revolutionary War. Well over two hundred years after the fact, it’s possible to envision how East Falls figured in the ebb and flow of the Revolution. (For convenience, this article uses contemporary place names, even though not all of them were in use during the Revolution.)

In the summer of 1777, after a British fleet was spotted off the coast of Delaware, the rebellious colonists suspected that the British would land nearby and try to take Philadelphia from the south. Washington repositioned some 11,000 members of the Continental Army, then camped in New Hope, to be closer to Philadelphia. On August 1, they set up camp roughly where the Queen Lane Reservoir and the water treatment plant now sit. People who walk their dogs along the edge of the reservoir know that this is high ground, offering views of downtown Philadelphia. In addition, the site is a short distance from two well-traveled highways — the old Ridge Road (now Ridge Avenue) along the Schuylkill, and Germantown Pike about a mile East of the site. All in all, this was a safe spot that provided a quick route for communications and supplies.

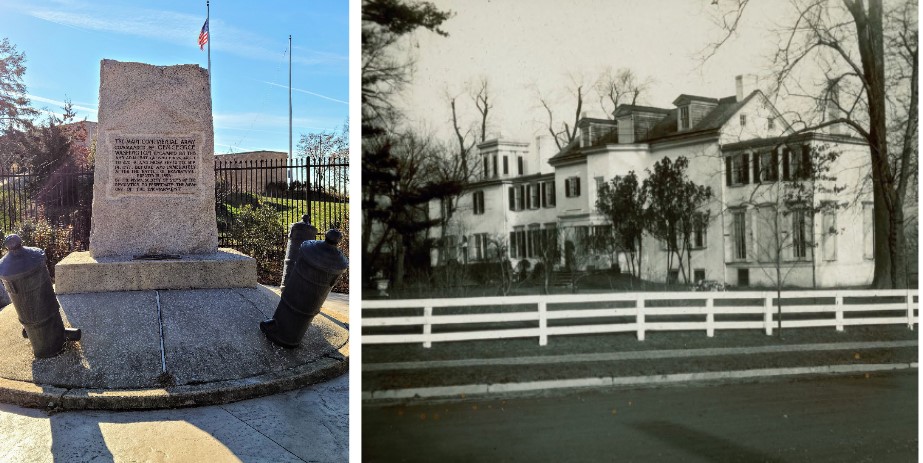

George Washington, with the newly commissioned Marquis de Lafayette in tow, came up to East Falls from Philadelphia on August 4. He set up his headquarters in the home of a wealthy patriot, Henry Hill, near the modern-day Stokely Street and Midvale Avenue. Hill’s home, enlarged or rebuilt, became the mansion Carlton, demolished in 1948, a major preservation loss. Carlton Park apartments now occupies the site.

Washington and Lafayette inspected the troops on August 7, and the following day they sent the army farther upriver to Whitemarsh. We don’t know exactly why this move was made – possibly Washington decided, based on his inspection, that the troops would be better off there. (Lafayette returned to the Whitemarsh site, this time in a command role, in 1778; many of us have driven past the roadside historical marker on Ridge Pike across from Barren Hill Road that commemorates this encampment.)

British troops under General Howe landed on the north shore of the Chesapeake Bay on August 25, and as feared they did start marching toward Philadelphia. Colonial troops met the British force about 30 miles south of Philadelphia. Unfortunately, at the Battle of the Brandywine on September 11, they were routed. By the night of September 12, after what must have been an exhausting 48 hours, they had retreated back to their campground in East Falls, and they stayed there just two nights before moving farther up the Schuylkill once again. The monument at Queen Lane and Fox Street commemorates the two encampments.

Less than a month later, our neighborhood played a minor role in the disastrous Battle of Germantown. Based on Washington’s orders, a colonial force led by General John Armstrong came down what is now Ridge Pike and crossed the Wissahickon Creek to the East Falls side before turning up the creek toward Germantown. Accounts of the Battle of Germantown indicate that British soldiers were standing guard along School House Lane from the Schuylkill all the way into Germantown. Anyone who’s gone down Gypsy Lane or Wissahickon Avenue knows that there’s a long, steep, wooded hill between School House Lane and Wissahickon Creek, so presumably Gen. Armstrong’s troops went undetected. But, owing to misadventures by other units, the Battle of Germantown was another terrible defeat for the colonists.

So this President’s Day, hop in your car or put on a good pair of walking shoes. Even though the built environment has changed, the topography tells a vivid story that’s worth another look. George Washington slept here, and history was made here.

Hearty carriage house survivor remains on School House Ln.

East Falls NOW, April 2022, by Steven J. Peitzman

A stone stables/carriage house from 1889 can be seen from the sidewalk of School House Lane if one looks down a driveway leading into to the squash center on the north campus of the William Penn Charter School. It recalls the Gilded Age history of that old and historic road.

Beginning in the early 1800s, affluent Philadelphians looked to Germantown and particularly School House Lane as a desirable location for a country home. By the later nineteenth century, merchants and manufacturers had created estates with finee houses along this stretch, giving them arboreal names such as “The Chestnuts,” “Blythewood,” “The Pines,” “Pinehurst,” “Glenwood,” and others – denoting that their wealth had attained life in a green, shaded place. Among the new owners was a textile importer and manufacturer named Edward T. Steel (1835-1892), who in 1875 acquired land on the north side of the Lane, not far from Wissahickon Avenue, on which stood a modest house. He engaged a noted architect, Addison Hutton, to transform the small structure into a colorful Queen Anne style mansion. He named his flamboyant house and its grounds “Woodside.” Atlases show that a small wooden stable or barn already existed on the property; in fact, all the estates had some such appendage, since horses and carriages were essential to get around.

In 1889, Mr. Steel again engaged Hutton, this time to design a new stables and carriage house, to be two stories, of good size, built of stone, and with a slate roof. Why did he wait fourteen years to make this costly improvement? An answer appears in his will of 1889, in which he lists his most cherished possessions, among them five “expensive mares of high pedigree recently purchased by me for stock purposes.” Steel was a horse fancier, and wanted a substantial and dignified home for his five high-caste ladies. He also owned some workaday horses, and a few cows. The second floor likely housed the coachman.

In 1917, many years after Steel’s death, the family sold Woodside to Francis R. Strawbridge (1875 – 1965), of the retail family. After the passing of the last Strawbridge to live there, the property was sold to the William Penn Charter School in 1984, mainly for the grounds. Finding no use for the main house, after a year-long preservation battle, Penn Charter demolished it, along with several small buildings. Somehow, the stables/carriage house was spared, and is in use by the school.

When photographs were shared with several architects and architectural historians, all admired this building as solid and handsome. Its prominent features include the large carriage door; the very intricate roof comprising intersecting hipped elements with small “gablets”; and the two ventilation structures emerging through the roof, one a small spire topped with weather vane and compass rods. With almost all of the more than twenty big houses of School House Lane gone, a few lesser structures recall its unique history. EFHS member David Breiner, of the Jefferson East Falls faculty, is nearing completion of a book which will explore in detail the architecture and social history of the section of West School House Lane familiar to Fallsers.

Street names reflect history of East Falls

East Falls NOW, May 2022, by Rich Lampert

People who look at maps are generally seeking geographic information – directions, distances, and such. In addition, street names often provide insights into history. This is certainly the case for East Falls, and this month’s article from East Falls Historical Society offers a variety of stories from different parts of our community.

Some months ago, the EFHS article talked about the “mayor streets” in East Falls – Conrad, Vaux, Henry, McMichael, Fox, and Stokley. These honor the first men who were mayors of Philadelphia immediately after all of Philadelphia County – including Roxborough Township, which included the area we now call East Falls – was consolidated into the City of Philadelphia.

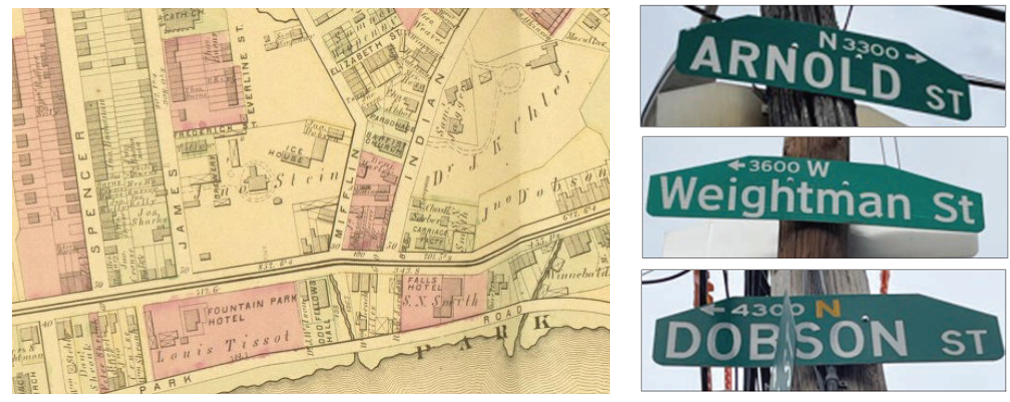

Other street names honor prominent people who lived and/or worked in East Falls. These include Dobson Street, named for the family that owned Dobson Mills. Two street names recall the onetime pharmaceutical giant Powers & Weightman. Powers Street, a little stub that runs up from Coulter Street into the side of a hill below the Jefferson soccer fields, was placed on the map in 1891. It was not until 1950 that a Weightman Street was put on the map, within the post-World War II “new houses” development.

Arnold Street is another stub of a street, running off Midvale Avenue into the side of a different hill. Dug into that hill were caves used to store beer from the nearby brewery, and the street previously was known by two different names – Brewery Street and Hohenadel Street – the latter for one of the brewery’s owners. In 1921, according to City records, the name was changed to Arnold Street, apparently named after Michael Arnold, then the proprietor of the Falls Hotel (now the location of the 7-11 at Ridge and Midvale.) Presumably Mr. Arnold was a major client of the brewery. It’s also possible that the name comes from the innkeeper’s son, also named Michael Arnold, who served as a judge in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas. Supposedly the future Judge Arnold actually lived in the Falls Hotel as a boy.

Some street names honor land owners, and run across land they once owned. Examples include Krail Street, named after one Dr. Emmanual Krail. Another was William Merrick, whose name became a street name in 1928. William G. Warden and family owned large tracts into the 20th Century, so we have Warden Drive, established in 1912.

Netherfield Road, running one looped block up from McMichael Park, recalls Netherfields, one of the earliest country estates along School House Lane, dating from the late 1700s and once known for its fine variety of trees. Over twenty estates came to line School House Lane over the next 150 years, though almost all their houses have been demolished. Exceptions include Roxboro House (now the Specter Center at Jefferson University); Ravenhill; and Ivy Cottage and the Brown/Hohenadel/Timmons house, both now with addresses on The Oak Road.

Sometimes names disappear from streets, and there are two prominent examples of this in East Falls. One is School House Lane. This road was once called Bensell Lane (or Bensell’s Lane), named after Dr. George Bensell, who owned a home near what is now Germantown Avenue and School House Lane. Sometime after Germantown Academy opened in 1760, the road became known as School House Lane. This might have been a gradual process, since some accounts of the Battle of Germantown (1777) still refer to this important thoroughfare as Bensell’s Lane.

The other example of a vanished historical name is now called Midvale Avenue. At one time, it was a short dirt road leading up from what is now Ridge Avenue, and it was called Mifflin Street. This name honored the first governor of Pennsylvania, Thomas Mifflin, and his estate (now long gone) which sat on a hill overlooking the road. According to City records, the name of Midvale Avenue – all the way up to Wissahickon Avenue – was put on official maps in 1889.

Gov. Mifflin wasn’t forgotten on City street maps – far from it. In 1878, even before the name Midvale Avenue appeared, the name of the east-west street at 1900 South changed from Southwark Street to Mifflin Street. Oddly, according to phillyhistory.org, other streets also used the Mifflin name at various times – even the street we now know as Walnut Lane, as well as a one-block street in Center City now called Kimball Street, which opened in 1901.

So street signs provide more than geographic information. They are clues to history.

Here’s a ‘fish story’ from the EFHS — complete with cornmeal and metal

East Falls NOW, June 2022, by Rich Lampert

After a long winter and up-and-down Spring, the Memorial Day weekend and the month of June hopefully are the start of a season for outdoor activities. In East Falls, that means that many of us are thinking about the Schuylkill River. Readers of East Falls Historical Society pieces in East Falls NOW probably know very well that East Falls has always been a place associated with fish and fishing. We’ve recounted plenty of stories about catfish and waffle dinners at East Falls inns, and, of course, the steeple on our library is topped by a catfish.

EFHS Board member Lyda Doyle remembers fishing in the Schuylkill in the mid-1950s with her brother David using homemade poles. Their father, David Furman, made bait from cooked cornmeal mixed with molasses (so the fish could smell it, he said.) Mr. Furman also made his own “dipsie” weights by melting metal and putting it in small molds. The catch included carp, sunfish, and catfish. Some folks – but not the Furmans – would take catfish home and have them swim around in fresh water for a few days to help leach out the toxins, then they’d cook and eat them.

A recent effort to acknowledge the role of fish in East Falls history took place in the late 1990’s, somewhat by accident. Community leaders hoped to raise money to light the Falls Bridge in honor of its centennial in 1995, but fundraising came up “way short.” (Eventually the bridge was lit, but that’s another story.) Still, there was a bit of money in the bank. One day, longtime community volunteers Keith Shively and Tom Williams were touring the Fairmount Waterworks behind the Art Museum when they noticed metal plaques commemorating important industries in Philadelphia. Gradually the idea emerged to similarly commemorate the fish that swam in the river off East Falls.

After many committee meetings as well as conversations with Steve Sears of Sears Iron Works in Ottsville, Pennsylvania, the a plan arose to create five plaques to recognize the major species – small-mouth bass, carp, channel catfish, striped bass, and yellow perch. Sears took the idea and ran with it: he devised the design for the cutouts that we now see along the river under the Twin Bridges. (A man named Bill Burke of the Philadelphia Art Commission suggested tilting the cutouts so that viewers would see water flowing behind the silhouettes.) East Falls being East Falls, funds were tight, and the pieces weren’t made until Penn Fishing Reels – that is, Herb and Gayle Henze – promised a five-year flow of funds to provide for maintenance.

The plaques were installed and dedicated sometime in the Fall of 1998, and the maintenance fund was quickly tested. Hurricane Floyd wreaked unprecedented havoc in mid-September 1999, and one of the casualties was one of the year-old fish plaques along the river. Steve Sears, the metal worker, fabricated a replacement in about a month. According to an oral history conducted with Shively and Williams, as the replacement was being installed, someone spotted the missing plaque on the bottom of the river. It’s no longer at the bottom of the river, but it’s not clear where it is.

Ready to pick up a fishing rod and try your luck?

Who knew? New bricks reveal East Falls’ past

East Falls NOW, July 2022, by Wendy Moody

It’s amazing what insights into our neighborhood emerge from the back stories of the newest bricks in the Falls Library garden walkway. The Buy-A-Brick campaign, recently completed by the Friends of Falls Library, added 185 bricks, all with creative inscriptions. Beyond tributes to loved ones (two and four legged), some conveyed revelatory glimpses into East Falls’ past.

Take these four …. in a way, they all have library connections.

East Falls: July 1, 1916

This brick, purchased by Joe Terry, commemorates the date Falls of Schuylkill officially became East Falls, according to Joe’s research.

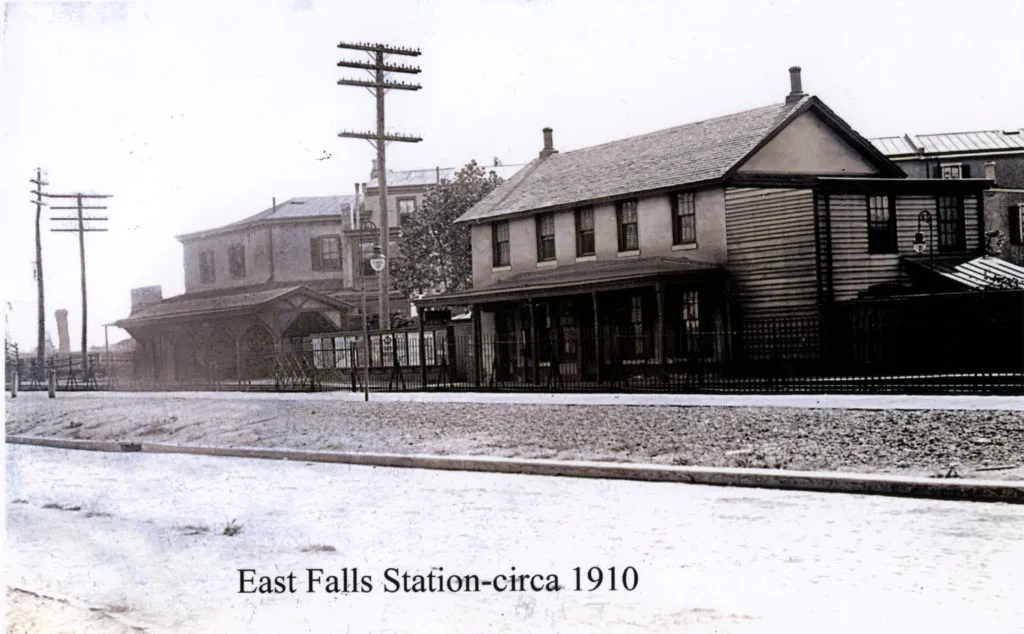

The “falls” – water rushing over large rocks in the Schuylkill near the railroad bridges – were submerged in 1821 when the dam was built downstream. Still, the name Falls of Schuylkill stuck. The Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad stopped at Falls of Schuylkill and, by mid-19th century, it was known as “Falls Station.”

Across the Schuylkill was West Falls – possibly a passenger station, but mainly where trains of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad could either cross the River to climb through Falls of Schuylkill toward the anthracite docks at Richmond; or follow the west bank into Philadelphia. To avoid confusion with “West Falls,” the Reading officially listed the station on the east side as “East Falls.”

The post office followed suit. The July 6, 1916 Weekly Forecast reported: “The local post office – known as “Station Z” – has changed its name to “East Falls Post Office.”

With both the post office and the train station designated “East Falls,” this became the generally adopted name for the neighborhood on July 1, 1916. Hence the brick.

Somehow the Falls of Schuylkill Library escaped the change — the last vestige of our former name.

Harry Prime, ‘40s Singer

This brick commemorates local legend Harry Prime, b. 1920 at 3512 Bowman in East Falls. Prime achieved acclaim as a big band vocalist with four renowned bands. He recorded nearly 100 songs in the 1940s – 50s, including “Until,” a million-seller with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra.

Prime, a born storyteller, was interviewed by the East Falls Historical Society, colorfully describing growing up in East Falls. (his oral history can be accessed on the EFHS website).

Prime aspired to be a professional ballplayer (“I was a hell of a catcher”) but, at 5’8” and 150 lbs., Connie Mack rejected him: “Harry, you have all the tools, but how much do you weigh?” Brooklyn reiterated: “We love you but you’re too small to be a major league catcher.”

So Prime pursued his other passion. Winning a singing contest led to an engagement at The 400 Club, becoming a backup singer for Jimmy Dorsey, appearing on the Chesterfield Show, and eventually, his big band career.

In his 90s, Prime returned to Falls, performing several cabarets at Epicure Café on Conrad. Ironically, Prime once lived above the café when it was Clayton’s Market, working there in his youth. If you listen to Sirius XM, Prime can still be heard on the Forties station (71).

It’s befitting that Harry Prime is “outside” the library – a rowdy teen, Prime recalled the library guard asking him to go “outside” many times…

Ellen Greco 1913, Diorio’ Grateful’

This brick, purchased by Kim Schuyler, honors her grandmother, Ellen Greco Diorio who learned English at the newly-opened Falls Library in 1913. Ellen was ‘Grateful’ to the “library teacher” who so dramatically influenced her life.

Arrivinghere from Italy in 1909 at age 3, she lived at 3632 Stanton Street, and attended St. Bridget and Breck School.

Ellen told her granddaughter: “In 1913 I was sledding down a hill on half a wooden barrel and nearly ran into a woman who had just gotten off the trolley on Midvale. She was walking to the library and invited me to join their reading classes. It was a turning point in my life.”

“The teacher taught us to get lost in reading – to close our eyes and imagine being part of the stories, saying reading could take you anywhere if you pictured it in your mind. She closed a window shade and then opened it to show how reading would open our world. We read Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves. It opened up my world.”

Kim reminisced, “My grandmomloved sharing memories of her wonderful teacher. I hope the teacher knew how much she was appreciated by my grandmother and, I’m sure, by countless other children. My grandmother, a lifelong reader, died at age 104 in 2010.”

Many immigrant families were coming to East Falls from Ireland and Italy, so these classes filled a need. Until now, we had no record of early programming at the Falls Library: this brick was a revelation.

Theo’s First Word, “Book”

What better tribute to the library? This brick was purchased, lovingly, by 14 month old Theo’s proud grandmother, Lisa Alandt.

Each engraved brick in the walkway tells a story – a personal or a community one. May they all be engraved in our collective memory.

A kid’s view of summer in East Falls, circa 1950’s

East Falls NOW, August 2022, by Lyda Doyle

After we woke up and ate breakfast, we had a world of choices, and none of them involved screen time — aside from a black-and- white TV here and there. Here’s a selection of what we did:

We rode our bike alone or with friends, who we’d meet at the usual rendezvous point.

We roller skated, but we couldn’t forget our skate key.

We played out front. Games included tag, red rover, Mother May I, wire ball, stick ball and hopscotch.

On Plush Hill, now known as Krail and Haywood Sts. overlooking the Roosevelt Extension of I-76, we could pick mulberries from the tree and eat them, or we’d take extra berries home in a clean glass milk bottle to be eaten later with milk and sugar. Or we could help the older kids build a fort and try to round up any supplies they needed (wood, nails, etc.) At night (yes, we went outside at night, too) we would try to catch lightning bugs, bring a candle for telling stories in the fort, and watch the fireworks exploding from across the river at Woodside Park on Friday nights.

In the Mifflin School yard, we’d bring a stick and “pimple” ball to play stick ball, bring a stone to mark our place in hopscotch, bring a jump rope (long enough to play Double Dutch if needed), and/or a ball for wall ball, or marbles for marble shooting contests.

The abandoned Hohenadel brewery formerly at Conrad St. and Indian Queen Ln. or the caves in Dutch Hollow at the top of Arnold St. were prime candidates for exploring. The brewery “ruins” could be hair-raising. Kids were somehow able to gain access to the inside from the loading dock on the Conrad St. side of the brewery. We played tag and hide-and- seek in there. Sometimes you would be chasing someone and grab a railing to go downstairs, but suddenly there were no steps and we had to grab the railing with both hands and arms to save ourselves. Once was enough for that! The getaway route was to slide down the railing to the first floor, which was a pretty good drop. Some kids would hide inside the old brewing vats on the basement level, and some of the older kids would get up on the top roof by an outside metal ladder and then slide down the rain spout.

At McDevitt Playground or Inn Yard, we’d bring a baseball bat and glove for pick-up games. If you didn’t have your own glove and bat you could borrow one from the other team when they weren’t using them. Sometimes we would just play on the swing. At McDevitt, we also could play on the steel merry-go-round. Kids sometimes flew off, but it was very close to the ground, so no one got hurt.

We would hike in the Chamounix Woods, across the Falls Bridge, or go swimming in The Bathey – later to become the Trolley Care Café and now Boutique River Falls.

Monday, Wednesday and Friday were Girls Day; Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday were Boys Day. Sundays we would sneak in. We would wait outside in line for our turn in a one hour “rank,” leaving and getting back in line again and repeating until the pool closed for the day.) In the Wissahickon Creek we would just foray up there and wade or swim in “Devil’s Pool.” The older teens might go swimming in the Schuylkill.

Fishing in the Schuylkill was always an option.

We would play hide and seek after dark under the streetlights that had been converted from gas to electric lighting. Parents and neighbors were out on the steps and porches chatting and watching.

And we always were in a hurry, because we knew that in the blink of an eye it would be time to go back to school.

September

EFHS shares remembrances on Old Academy’s 100th year

East Falls NOW, September 2022, by Wendy Moody

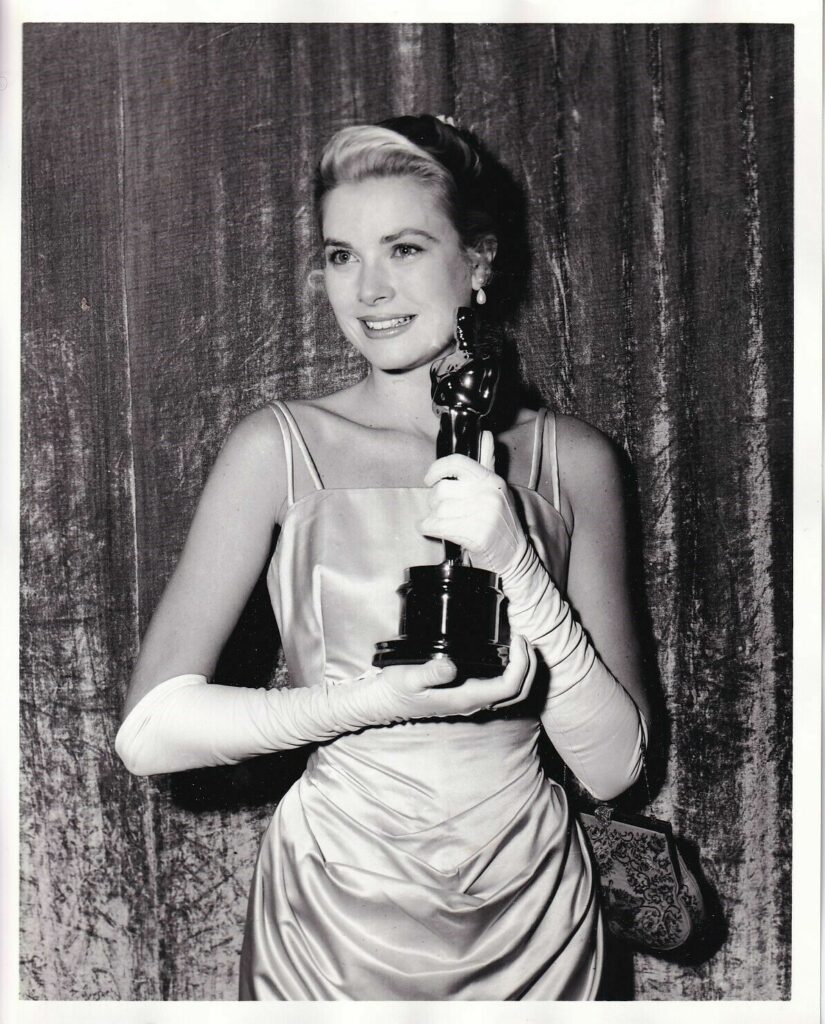

The East Falls Historical Society congratulates the Old Academy Players on its 100th season of entertaining our community. Enjoy these engaging snippets of Old Academy history that we found in our EFHS oral history interviews with our residents. Many Old Academy memories involved Grace Kelly – these will be featured in our November column, Grace’s birth month. (These are reliable recollections of OAP members who were there, but they have not been independently “fact-checked.”)

On the Old Academy Player’s Formation

“There was a group at the Falls Methodist Church on Indian Queen Lane called the Queen Esther Circle. To make money for the church, they put on a musical play in 1923, The Minister’s Wife’s New Bonnet. A great success! Other churches invited them to perform and the theater bug bit them. However, the minister at the very strict Methodist Church didn’t want them using the church’s name when giving plays – it was not in keeping with their beliefs. So the group named itself the Moment Musical Club and began meeting at homes, rehearsing in the Falls Library, and renting Palestine Hall at Ridge and Midvale to perform.

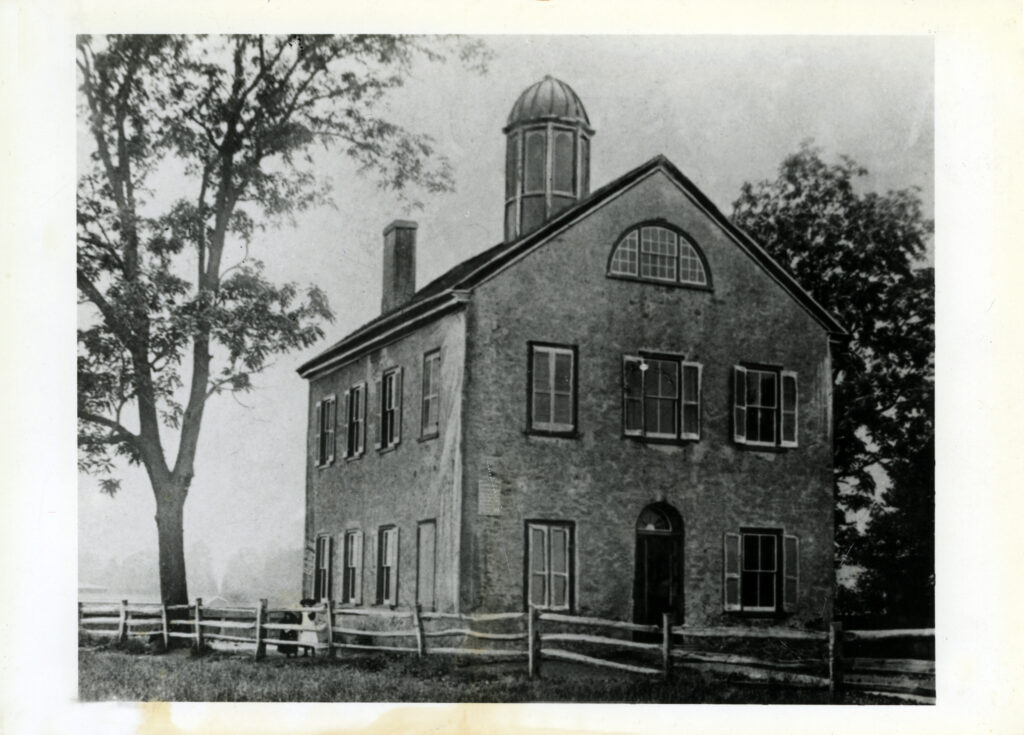

In 1932 the board of trustees of the Old Academy building asked the Moment Musical Club if they would like to occupy their building. Delighted, they purchased it for $1.00 and changed their name to Old Academy Players. They repaired the dilapidated building, created a theater on the first floor, made a curtain – everything was done by their labor – they had no money to speak of. They preserved the historical old building!” (Ruth Emmert, 1983)

The 1952 Fire

“My father was caretaker of Old Academy and when he died suddenly in 1949, I took over temporarily and ended up spending 33 years there – painting sets, making slipcovers. In 1952, they were painting the walls and I had come over at lunch time. The painters were outside eating, when someone said ‘There is smoke coming from under your roof!’ The fire department came, but the whole third floor – the roof was burnt right out. They said when they were chipping on the wall, wires must have crossed. All the water came flying down; all the clothes and play books went out the window! And then that dome up there -there were about ten firemen hanging on it trying to pull it down thinking the fire would be up in there. And then the women said “Don’t tear that down! It’s a landmark!” (Mae Mohr, 1983)

“Yes, we had a bad fire. The cupola was damaged, the attic was destroyed; there was over $10,000 in damage…. But we were insured and whenever we have troubles – we’re a close-knit club – we band together. Everybody cleaned up. There was a hole in the roof. They placed a tarp over it and managed to go on with the play – Three is a Family – just a week later.” (Robert Freed, OAP Historian, 2009)

Old Academy Players Charity

“Old Academy always did charitable stuff. Among them: The Nov.1, 1940 minutes read: “A motion was passed to give $2.40/week for milk to needy children at Mifflin School.” In

November 5, 1940: “Members are contributing fifteen cents a week for children who are refugees from the European war.” In war years they took shows to Camp Dix and the Naval Hospital. One interesting suggestion during the war (8/13/42): “Cast women in male parts because of men going to war This was defeated, fortunately!” (Robert Freed)

Not in the Script

“During the Depression, we performed Liliom, which later became the musical Carousel. One of our members was out of work and offered to live in Old Academy, do the work, direct the plays, build the sets – this was great. He had a pet cat – very black – named Inky. Anyhow, Liliom has died and they come to get him – all dressed in black and very solemn. They march with a measured stride onto the stage to take him to the hereafter. And this one night, as the music swelled for their entrance, the first to enter was Inky, with measured stride and black tail high in the air. He led the men from heaven or hell or wherever across the stage to get Liliom… the audience roared.” (Ruth Emmert, 1983)

A Chance to See Two Modernist Gems in East Falls

East Falls NOW, October 2022

[This article included a notice of an Oct. 2022 tour, led by David Breiner, PhD of Jefferson University, and Alison Eberhardt, MA, an architectural historian and photographer.]

The central section of East Falls – the old “Falls Village” – is known for its 19th-century row houses and twins, many in the Italianate, Gothic Revival, and Second Empire styles. Going up the hill, an alert visitor will enjoy seeing our Tudor East Falls Historic District, our unusual Spanish Revival rows, and, finally, the many fine Tudor and Colonial Revival houses east of Henry Avenue, the area once known as “Queen Lane Manor.” But East Falls also can boast of important “Mid-century Modernist” houses (and also a former nurses home and a fire station in Modernist mode). What has come to be called “Mid-century Modern” overlaps with an architectural approach also referred to as “International” or less commonly, Miesian, after the prominent architect Mies Van der Rohe. Such design, broadly understood, aims at clean lines, use of the steel frame to allow glass walls, an “open” floor plan, and minimal ornament.

The Modernist houses of East Falls are mostly to the north, along School House Lane and Apalogen Road. Among them are the Hassrick House and the Rothner House, both of which will be visited on a tour organized by the East Falls Historical society for Saturday morning October 15 [2022]. Designed by internationally-recognized California architect Richard Neutra, and now part of the Jefferson campus, the Hassrick House exemplifies Modern architecture as it was widely produced in the decades following World War II. Though currently unfurnished, it is still an impressive residence. The Rothner House is owned by architect and aficionado Janet Grace, who has furnished it with excellent examples of Mid-century Modern design. This building was created by respected local architect Norman Rice, known for important contributions to the “Philadelphia School” of Modern architecture.

East Falls residents recall Grace Kelly

East Falls NOW, November 2022, by Wendy Moody

As Grace Kelly’s birthday on November 12 approaches (she was born in 1929, died in 1982), enjoy these unique personal glimpses of her earlier years, extracted from the EFHS oral history collection:

Ruth Emmert (Old Academy Players; 1983 interview):

“Gracie was one of the kids in Don’t Feed the Animals when she was nine. That’s when the theater bug bit her and she knew she wanted to be an actress. She kept coming around and trying.

One day backstage, while Grace was putting on makeup, I said “How old are you, Gracie?” She said “14.” I said: “14! You’d never know – you look 18, 19, 20 – your height, your poise – I would say you were much older. You’re so grown up for 14!” She replied, embarrassed, “I’m not really 14, I’m only 12…”

Well she looked 18 – her hair worn in the bob of the day, that sweet smile, and sparkling blue eyes. She was tall for her age, very slender, dressed beautifully but casually. She was not shy, just not pushy, and had a great sense of humor.

She wanted to get a part and, for that, she worked. She was utterly reliable, knew her lines perfectly, never missed a rehearsal, and helped with props – emptying her mother’s closet of negligees and gowns for the cast, and lending furniture for the sets. She was a joy.

When her father donated money and bricks to build a theater addition, we asked him what we could do for him. He said “Give the kid a part once in a while. She wants to be an actress.” But Old Academy didn’t give her special attention. And so she didn’t get parts. Once she asked me: “What do you have to do down here to get parts?” I said “The only advice I can give you, Gracie, is to be visible – come to business meetings, plays, and club nights.” Gracie came down and came down. She sold chances; she was working all the time. She certainly deserved all the parts she’d get.

I don’t think she was naturally talented for acting – it was just learning, hard work, and stick-to-it-ness. And of course her beauty, which she had. Her inner and outside beauty was always there. And that helps.

Joe Petrone (2013 interview):

Ah! I was in love with Grace. In 1953, when Mrs. Kelly held the Rose Carnival in front of the hospital [Woman’s Medical College], my job was to ride in the back of a Buick convertible with Grace Kelly and sell chances for the Carnival. We rode through East Falls with a blaring speaker and I would sit there in the back seat and just gawk at her. I was in love with her. I was maybe nine. She was very pretty!

At the Carnival, somebody brought a gold compact to our booth and said “Grace gave you this to sell.” It was engraved ‘Grace Kelly.’ It was hers! It was five bucks – a million dollars in those days. I wanted that so bad, so bad. And I didn’t get it. But she was a beauty…

Peggy Kelly Conlan (Grace’s older sister; 1981 interview):

I took over for Grace in The Women at Old Academy when Grace got the measles. On the night of dress rehearsal, we were sitting at the dining room table and Mother looked over and

said “Gracie, you look a little flushed and funny.” She was breaking out just then and she had a fit! Right before the big night she comes down with the measles! She was about 12. Grace had just a few speaking lines so it was easy to take over.

Edie Gotwols (Old Academy Players; 2009 interview):

Grace was a bit on the quiet side. She was lovely. One day at Old Academy she was sitting next to the prompter, who looked down and said “Grace, you have runners in your stockings!” and Grace said: “My mother makes me wear them.”

Harry Prime (2012 interview):

I would go to mass purposely to sit near the Kellys. Jack was 6’2 – a big guy. He would walk in, Margaret next, then all the kids. He was like the Van Trapp father. I made sure I sat right behind them. I would look at Grace and say “Good Morning Grace” and she would say “Good morning.” Grace was a striking beauty. When people bring up the prettiest actress, many names are mentioned – Ave Gardner, Lana Turner…. but Grace was striking. (2012)

Robert Freed (Old Academy Players; 2009 interview):

In 1955, just after she had won the Academy Award [The Country Girl], Grace Kelly came to Old Academy for the last time to see her sister Lizanne in The Moon is Blue. She took an interest in the club – donating money, and sending us a telegram thanking us for our congratulatory note when she won the Oscar. Old Academy usually gets mentioned in her biographies, because this is where she started.

Historic Designation in Philadelphia: Meaning and Myths

East Falls NOW, December 2022, by Steven J. Peitzman

Recent years have seen residents of Roxborough, our neighboring community, enthusiastically add three historic districts to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places – the Ridge Avenue Thematic District (2018) and the recent Victorian Roxborough Historic District and Gates Street Historic District (both 2022). These comprise mostly residences, built from the 18th to the early 20thcenturies. The motivations were pride in historic streets and houses, but also development and rampant demolition. As recently reported in the Inquirer (15 November 2022), residents of Powelton Village placed over 800 properties, mostly homes, on the register as an historic district.

Twenty-one sites in East Falls are on the Philadelphia Register. Added over the last five years include: “Palestine Hall” (built as an Odd Fellows hall), The Falls of Schuylkill Library, the Brown/Hohenadel/Timmons House on The Oak Road, Manor Sunday School/Church of the Good Shepherd chapel on McMichael Street, the Memorial Church of the Good Shepherd on The Oak Road, a stone “Gothic Cottage” on the Penn Charter Campus, the Alexander Henry House on School House Lane, the Alexander Henry Carriage House and Stable with address on Warden Drive, the Woodside Carriage House and Stable on the Penn Charter Campus, and the Falls Bridge. Several of these nominations were produced by the EFHS. For information on most of these and other sites, go to eastfallshistoricalsociety.org. The Tudor East Falls Historic District, comprising 210 houses on the 3400 blocks of Midvale Avenue, West Penn Street, and Queen Lane, was listed in 2009.

Why do we have a Philadelphia Historical Commission and a Register of Historic Places? The relevant section of the Philadelphia code (14-1000) says this:

It is hereby declared as a matter of public policy that the preservation and protection of buildings, structures, sites, objects, and districts of historic, architectural, cultural, archaeological, educational, and aesthetic merit are public necessities and are in the interests of the health, prosperity, and welfare of the people of Philadelphia.

In other words, historic preservation is a public good. What does listing on the register mean for a house, church, commercial building, or district? Let’s answer some of the questions commonly raised about the preservation process in Philadelphia, with homeowners in mind:

How does a property become designated for listing on the register?

Any person, organization, property owner, etc. can write a nomination to place a property on the register. A prescribed format must be followed, and the historic and/or architectural merit must be adequately supported by research. Examples may be accessed on our website. The nomination is reviewed by PHC staff, a designation committee, then the full commission, which votes to designate or not.

Is the property owner’s permission needed?

No. This surprises, even shocks, many persons. Of course, it is desirable for owners to want to see their house or block recognized as historic, and protected. As in zoning and some other matters, public benefit may outweigh individual prerogative. But property owners often misunderstand what designation entails, so let’s continue…

When a building (and usually its lot, or parcel) is designated, is the owner required to return its appearance to the time it was built?

No! At the time of designation, an owner need do nothing. But some subsequent alterations become regulated by the Historical Commission. Any property owner in Philadelphia is expected, by law, to maintain good repair.

What is regulated?

Owners need only maintain the external historic appearance present at the time of designation, including prohibition from demolition! Internal modifications are not regulated.

How does the process work?

Any request for a building (or demolition) permit by the owner of a designated historic property is sent by the Department of Licenses and Inspections to the PHC staff. The vast majority of permits for minor changes are approved by staff, sometimes after review with the owner. Staff can provide helpful advice, preferably before a permit is sought. For proposed substantial changes which would lead to significant impact on the essential historical appearance visible from public spaces, the request goes to the PHC Architecture Committee, and then to the commission itself. For the Tudor East Falls Historic District, from 2009 until 2020, only one request out of a total of eighty needed to go beyond staff review!

Does historic designation lead to a decrease in the value of a house?

Many studies have shown that values usually increase, assuming a viable neighborhood. Sale prices of houses in our Tudor East Falls Historic District have increased, and houses sell easily.

For more information, visit the website of the PHC at https://www.phila.gov/departments/philadelphia-historical-commission/, the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia at preservationalliance.com. We can answer general questions via eastfallshistory@gmail.com. And join EFHS! You can do so on our website. We have plentiful plans which need new members to make real.