East Falls NOW – 2025

Go Top January February March April May June July August September October November December

ANOTHER SIDE OF THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR: OCCUPIED EAST FALLS

By Donna Husted Levy for the East Falls Historical Society

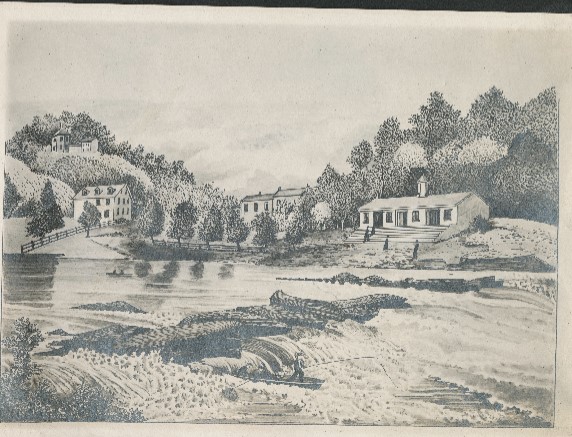

Last month’s issue of East Falls NOW included a long article about the sale and likely redevelopment of a property that was once part of the Garret farm, arguably the earliest European settlement in this area. This same property figured in a little-remembered occupation that occurred during the Revolutionary War.

Remember the Hessians? They are the German mercenaries who were routed by Washington’s troops in Trenton after the famous “Washington’s Crossing” on Christmas night, 1776. With the current Christmas season winding down, perhaps someone might wonder what became of the Hessians after 1776.

Very simply, they didn’t go away. Just nine months after their rout in Trenton, they were part of the British force that captured the city of Philadelphia on September 26, 1777. Most of the Hessians moved on to Falls of Schuylkill, living in huts that stretched along School House Lane, then called Bensell’s Lane, beginning at the Schuylkill and reaching all the way to Germantown. As the Hessians settled down in East Falls, Washington’s army kept moving, eventually setting up camp on December 19, 1777, the start of their miserable winter there.

The Hessians were not good or welcome visitors to Falls of Schuylkill. For instance, one battalion of Hessians encamped near the Garrett cabin (around modern-day Tilden and Vaux Streets), where Hessian Colonel Von Donop, it is told by family lore, made his headquarters. A handwritten ledger containing estimates of damage done by the enemy forces includes losses incurred on Garrett’s land, a farm that also included established orchards, livestock, and a cider mill. These losses are listed at 497 pounds, 9 shillings, 6 pence (roughly $89,000 at 2024 currency levels.)

British Major John Andre kept a diary account of the Hessians’ plunder: This quote appears in the book The Life of Major Andre: “With the English privates, the Hessians did not get along pleasantly; arrogant, full of the idea of immediate allotments of land, and of living in free quarters with unlimited license to plunder. They incensed the inhabitants to such a degree that many a farmer thought little…when they had the opportunity to shoot a Hessian as a hawk.”

All around the Falls, there was damage done by the troops. The beloved fishing club, Fort Saint David’s, was empty during the occupation of Philadelphia, with many members involved with the war. By 1778, the club was a pile of ruins, the Hessians having used its materials for their winter huts. They then burned the rest of the building to the ground. This may have been the first time a building of historic significance would be destroyed in East Falls, but certainly not the last.

The Hessians were ruthless, but within the group one Major Burmeister found honor in the American fighter. He writes in his letters, “The American’s are bold, unyielding and fearless. They have an abundance of something which urges them on and cannot be stopped. Then their indomitable ideas of liberty, the mainsprings of which are held and guided by every hand in Congress. With little show the Americans will exert themselves to the utmost to gain complete freedom and they are by no means conquered.”

Roughly four years after the Hessians occupied East Falls, Cornwallis surrendered following the Battle of Yorktown, and the colonies were truly independent – a reminder that determined people can achieve great victories in four years.

About the author: The family lineage of Donna Husted Levy traces back to a Swedish family named Garrettson, later Garrett, who were among the first European settlers of East Falls.

By coincidence, some 300 years after Donna’s ancestors were granted this land, she and her husband purchased their first home on the 3400 block of Queen Lane, less than a thousand steps from where the Garrett cabin once stood. Donna is a member of the Swedish Colonial Forefathers and the Daughters of the American Revolution, and she and her husband currently reside in Wynnewood.

Do you have questions about East Falls history, or want to know more? See our growing website at www.eastfallshistoricalsociety.org or contact us at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. And join! You can do so on our website, eastfallshistoricalsociety.org.

MEDICAL STUDENTS IN EAST FALLS FIFTY YEARS AGO

By Alan Schindler, MD for the East Falls Historical Society

They sang for their supper. Every week or so the two young women would go down to Pete’s Cafe on Midvale near Ridge, walk down the alley to the “Ladies’ entrance”. Once inside, one would play the guitar and the other would sing for the patrons, and their reward would be dinner.

They were just two of the 64 recent college graduates or second-career women in the Class of 1970 at The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, located on Henry Avenue. These women were happy to be in what many remember as the warm, supportive atmosphere of WMC at a time when the number of women admitted to medical school was severely limited. While some came expecting to be in East Falls for only a short time and then to move on, some ended up staying almost forever. None of them knew in 1966 that they were destined to be in the last WMC class to graduate only women.

Recently I contacted as many of my former classmates as I could, and they responded with memories of how they lived outside of class, mostly in the late 1960’s. This column recounts some of their memories.

Long-time Fallsers might remember Pete’s Café on Midvale near Ridge, now Taqueria Cresta, but what else was there nearby where students could live, eat and shop? A survey of those women, now mostly retired and scattered across the country, stirred memories of that earlier time when, for example, there were trolley tracks, a movie theater (the Alden), and gas stations on Midvale where now stand apartment buildings.

Those young students rented apartments on Indian Queen Lane, School House Lane, elsewhere throughout the Falls, and across Wissahickon Avenue in Germantown. (A lot of East Falls property was owned by the barber Joe Michetti who, some might remember, would go up to WMC Hospital to give haircuts to patients.) Many women shared apartments. According to recent recollections, one had a “crummy apartment with a very small bathroom”; another lived in “an unheated basement apartment”. Some students lived in the sorority-owned Zeta Phi house, one half of a twin on Fox at Penn Street, with its extensive house rules, including “don’t use the third floor shower because it leaks into the second floor.” At least one student would sometimes stay all night in the library to avoid a one-hour commute home. Many lived within walking distance of the school, some drove, and some hung onto the backs of their friends’ scooters.

They occasionally ate out, and remember eating at Pete’s — 25 cents for a mug of beer — or Murphy’s (yes, our same Murphy’s), at the Pub at Henry and Allegheny, at Horn and Hardart’s in Germantown, or at the Chinese take-out Hung-Hing on Queen Lane . “Fine dining” when affordable, or when being treated by someone’s parents, could be had at the Open Hearth at Alden Park (where men had to wear ties and jackets, and which burned down mysteriously years later), Crane’s on Queen Lane, or Green Hedges on Greene Street. “Faculty were great at entertaining students with dinners at their homes.” Students would sometimes shop for food at the Tilden Market (now NouVaux), but mostly they would go to supermarkets in Roxborough or Bala. One, missing New York, would run home on weekends to stock up on food.

For spiritual and religious needs, institutions mentioned were St. Bridget’s Church, St. Mary’s Hamilton Village on the Penn campus, and the Germantown Jewish Centre. For entertainment, people reported the occasional movie or party with classmates, with some events at the Zeta Phi sorority. Or students would get together to hang out and listen to their own self-generated music. One reported just sharing tea with a classmate, while watching their cats stare at each other. And some who were married, and maybe not, remember engaging in various extracurricular, but not reportable, private activities.

And would you believe that the total tuition for four years was $6000? Even so, while a few students had parents or others who helped with their tuition and some got scholarships, many struggled, taking loans or getting jobs — one as “house mother” for a year at Zeta Phi; one as a church organist playing at weddings and funerals — to make their way through. Most worked during the summers after first and second year. Some had taken a year off before medical school and had saved up some money for tuition.

Most of East Falls, especially the residential areas, looks much as it did back in the mid-1960s. So, when they return, the familiar surroundings bring back fond memories to those women who became doctors here and went on to serve others for many years. But Woman’s Medical College, the center of their lives in those days, lives on only as remnants within Drexel University College of Medicine.

“ON ST. PATRICK’S DAY, EVERYONE IS IRISH, RIGHT?”

By Rich Lampert for the East Falls Historical Society

That’s what Tom Doyle says, and that explains why a large painted shamrock appears every year around this time in the intersection at Ridge and Midvale. At press time, Tom, who participated in painting the very first shamrock, is making preparations for the 66th consecutive annual job. Although Tom has moved north to Andorra, he remains loyal to his roots in the lower Falls, starting from his boyhood house on Laboratory Hill with no running water.

If the shamrock appears to be a more polished product than it was some years ago, that’s because it is. In the early days, paint was applied with ordinary brushes, a laborious process. To reduce the amount of labor, the shamrock creators tried spray paint – good results, but too expensive. Then came paint rollers, the method used today. Also, the materials have evolved, and currently the shamrock is created with durable highway paint. The painters have learned that going over the pavement with propane torches before painting heats the surface and helps the paint dry more quickly. Also, the size and shape of the shamrock are more consistent from year to year, as well: Tom created a durable template to define the shape, and painting the outline around the template is now the first step in the process. Once the supplies are in place, the actual painting takes about an hour.

Traffic issues aside, this isn’t an easy job. It’s tough to do in unfavorable weather conditions – not just rain or snow, but also on very windy nights. Road salt is the worst enemy of the shamrock. If the city has applied salt in a recent snow storm and it hasn’t been washed away in a subsequent rain, the paint doesn’t adhere as well to the paving, and the shamrock fades away too quickly.

Painting the shamrock started in 1960 with an idea by brothers Danny and Skip Grimes and their close friend Bernie Winters. Tom was younger – he was only 14 — but they agreed that he could come along, too. Tom now thinks of this effort as “the first graffiti,” but it became an annual effort that involved an evolving cast of characters. A few years after the shamrock custom started, Skip Grimes was the manager of the Spartans, an East Falls-based baseball team who for a time were the core of a group that sometimes grew to 30 or 50 people. In the early days, the crew drew the shamrock literally at midnight on March 17 itself. The effort quickly grew to putting out traffic cones and having people stand around the work site with flashlights to keep traffic away. Over time, the timing evolved, and the work now takes place in the middle of the night over a weekend, when traffic is lighter.

This has been going on for many years, and naturally participants in the painting have come and gone. Sometimes other groups have attempted to do the work: Once the shamrock was a well-established tradition, in some years people other than the original crew would take it upon themselves to paint it. According to Tom, they generally did a pretty rough job, so members of the original crew would show up later to fix it up.

Time has gone by, and the older originators – Danny and Skip Grimes, along with Bernie Winters – have passed away. For a couple of years after Danny Grimes died in the 1990’s, aged well into his 90’s, his in-laws, the LaPorte family, painted the shamrock in Danny’s memory before Tom and his family could get to it. Unlike other interlopers, Tom said, they did a beautiful job.

For the last 25 years, painting the shamrock has become an annual event for the Doyle family. At one time or another, all of Tom’s children have participated, and now some of his grandchildren as well. Currently, most of the painting is done by Tom Doyle, his brother Michael, and his nephew Michael Junior, with other members of the family holding flashlights and directing traffic.

The shamrock started out as a prank and has evolved into a community tradition. To that, all of us in East Falls can hoist a Guinness and say, “Slainte!”

Do you have questions about East Falls history, or want to know more? See our growing website at www.eastfallshistoricalsociety.org or contact us at eastfallshistory@gmail.com. And join! You can do so on our website, eastfallshistoricalsociety.org.